A country in drought and what we can learn from the past

Iran is facing a quiet yet severe environmental catastrophe. Decades of overuse of water resources, unregulated well drilling, and the construction of large dams have disrupted the groundwater balance, leading to dramatic consequences. In many regions, the ground is sinking. Land subsidence now affects large areas of the country, particularly around Tehran, Yazd, and Isfahan. Satellite images show that the ground in Tehran is sinking by up to 25 centimeters per year in some areas. This is not a slow, natural phenomenon but a direct result of the over-extraction of underground water reserves—many of them illegally tapped through unregulated wells and agriculture.

Bild: https://iranjournal.org/news/iran-gefaehrliche-bodenabsenkung

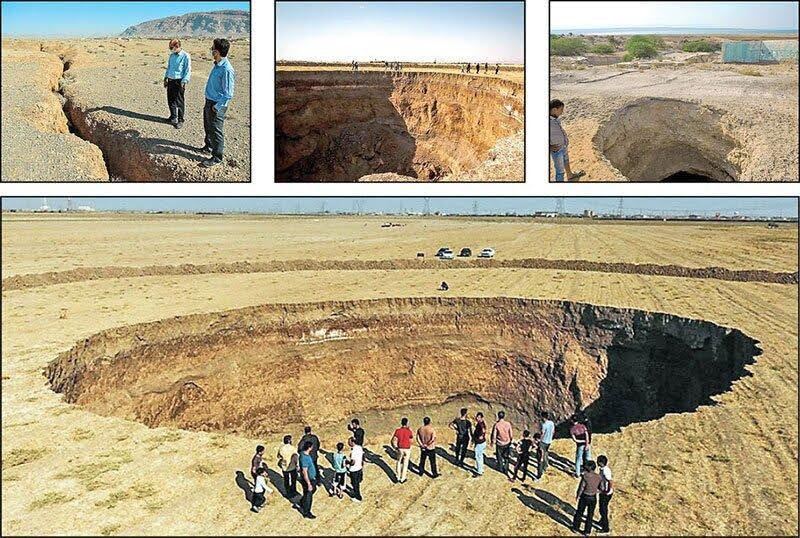

Bild: https://www.greenprophet.com/2019/02/irans-capital-city-being-swallowed-by-sinkholes/

The causes of the crisis

The causes are varied: Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iran’s population has grown from 37 million to 82 million. Additionally, a construction boom of dams has intensified the overuse of groundwater. However, the primary cause lies in unsustainable water management. Around 90% of Iran’s water is used for agriculture—often through outdated, open channels that result in significant evaporation losses. Meanwhile, natural reservoirs are shrinking. The groundwater level around Tehran dropped by 12 meters between 1984 and 2011. Rivers like the Zayanderud in Isfahan no longer carry water year-round, or not at all. Dam constructions upstream, coupled with water diversions to other regions, have harmed numerous ecosystems.

Faced with the crisis, authorities and farmers increasingly turn to deeper groundwater sources. By 2022, 320,000 illegal wells had been dug. But the deeper the wells, the more severe the damage: underground water is being extracted faster than it can be replenished by rainfall or inflow. The ground loses its elasticity, becomes permanently compacted, and begins to sink.

Historical and cultural impacts

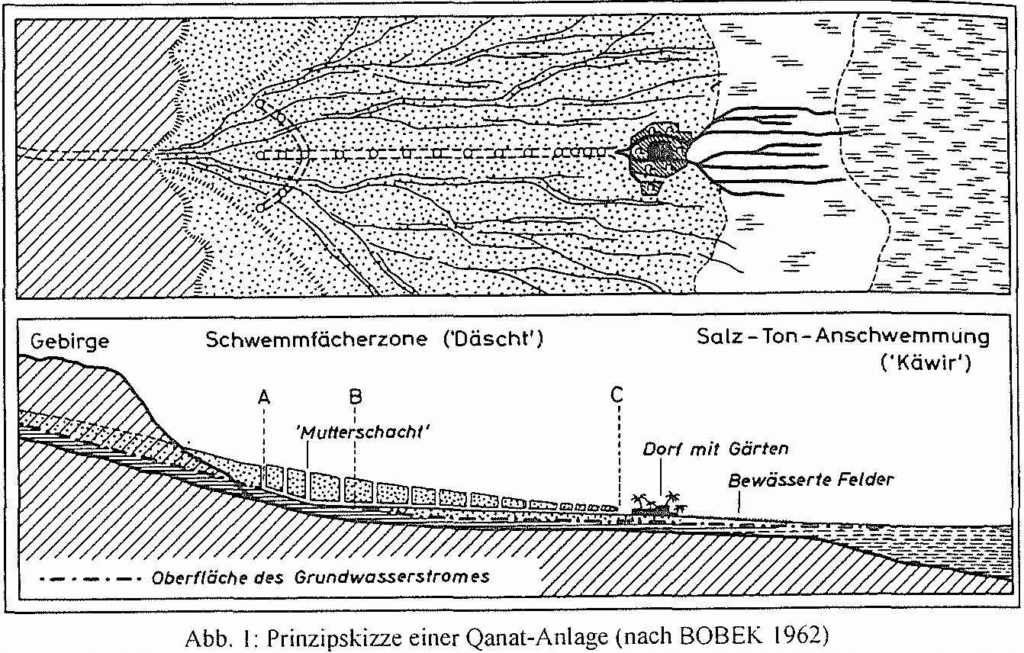

One of the consequences of this crisis is the destruction of historical structures. In Isfahan, cracks have appeared in ancient mosques and palaces. Even qanat shafts, ancient underground water systems, are losing their balance due to sinking soil and collapsing. These qanats, once a sustainable water solution, are now in peril, taking with them not only precious water but a part of the country’s cultural heritage.

Qanats: a 2,500-year-old sustainable solution

Qanats were developed over 2,500 years ago by Iranian engineers in the arid highlands of Iran. These underground channels use the terrain’s slope to bring water from the groundwater table to the surface—using gravity alone, without the need for pumps. Shafts for maintenance and ventilation are regularly spaced to the surface. Qanats were not only ingeniously engineered but also ecologically beneficial: They protected water from evaporation, prevented overuse, and enabled stable agricultural supply for centuries, even in desert-like regions.

At one point, Iran had more than 30,000 of these systems. Today, only about a third of them are functional. Many have been filled in, damaged, or simply forgotten. Yet, there is a growing international interest in this model—partly because similar systems exist in Latin America and North Africa. In Yazd, one of Iran’s driest cities, qanats are still in use. The city was even designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2017—partly because of its traditional water technology.

Could the future lie in the past?

Many experts say: Yes, at least in part. Rebuilding functional qanats could help use groundwater more efficiently and sustainably. But tradition alone won’t solve the problem. A radical shift is needed: modern water technology, efficient irrigation, rigorous water management—and above all, a culture of mindfulness in managing this vital resource.

Amena Agharabi, an Iranian environmental engineer, aptly writes in her study on greening potential in arid and semi-arid cities: “Tehran is swimming in a sea of wastewater, while the ground is drying up.” She argues that wastewater treatment could provide sufficient water not only for public green spaces but also for urban agriculture. Using treated wastewater and water from other sources like qanats and rivers could reduce water stress in the warmer months. Her call: Only a holistic, long-term plan—including the population—can secure the livelihoods of future generations.